Dr Norman

Claringbull

Psychotherapist

Counsellor

Psychologist

The Friendly Therapist

Call now for a free initial telephone consultation

Total confidentiality assured

In-person or video-link appointments

Private health insurances accepted

Phone: 07788-919-797 or 023-80-842665

PhD (D. Psychotherapy); MSc (Counselling); MA (Mental Health); BSc (Psychology)

BACP Senior Accredited Practitioner; UKRC Registered; Prof Standards Authority Registered

BLOG POST May/June 2016

Posted on April 30th, 2016

GETTING YOUR LIFE IN BALANCE

A very important psychologist called Albert Ellis, once noted how lots of people get themselves into quite a tizzy, indeed often into quite a panic, as they try to get all their jobs properly completed, all of their challenges resolved, all of their objectives reached.  And that’s just in the immediate, in the here-and-now. In the long-term, such restless people find themselves so continuously driven by life’s demands that they can never be still, never at rest, never take a real break. For these ‘performance worriers’, not meeting their targets is an absolute no-no. They are convinced that that this or that MUST be done – “I MUST get that wall painted by tea time”; “I MUST always be the best mum ever”; “I MUST go to work next week no matter what”. What Ellis also observed was that in many cases these ‘musts’ are nothing like as absolute as the worriers think they are. After all, not getting that wall painted today probably won’t be a disaster. Being the best mum ever is impossible. The world certainly won’t end if you miss a few days at work.

And that’s just in the immediate, in the here-and-now. In the long-term, such restless people find themselves so continuously driven by life’s demands that they can never be still, never at rest, never take a real break. For these ‘performance worriers’, not meeting their targets is an absolute no-no. They are convinced that that this or that MUST be done – “I MUST get that wall painted by tea time”; “I MUST always be the best mum ever”; “I MUST go to work next week no matter what”. What Ellis also observed was that in many cases these ‘musts’ are nothing like as absolute as the worriers think they are. After all, not getting that wall painted today probably won’t be a disaster. Being the best mum ever is impossible. The world certainly won’t end if you miss a few days at work.

Common sense tells us that in most cases, missing performance targets, especially the self-imposed sort, doesn’t usually cause catastrophes. It might be a nuisance, it might even be a disappointment, but rarely will it be a calamity. Nobody dies! The reality is that in most cases there are no significant penalties, (other than those in our imagination), if we are less than perfect. So, why do we worry so much, (and so unnecessarily), about getting everything not only done, but done perfectly, and done on time? Why do we have to be ‘the best’ – whatever that is. Clearly, if nobody else is actually threatening us then our fear of failure must come from within. In other words, our ‘musts’ result from our inner psychological needs. Put another way, “I must” often only means “I will feel better if I do”. This means that behaving as if “I must” is an absolute fact is actually an act of attempted emotional self-gratification. That is why Albert Ellis called people who feel compelled to act in this way ‘mustabators’.

The trouble with continually chasing our ‘musts’ is that doing so requires a huge amount of psychological and physical energy. This puts demands on us that far outstrip our personal resources. As a result, trying to meet these demands is an unending struggle, one that in the end we can never win. That’s why we become stressed and anxious. We are in a ‘loose – loose’ situation.

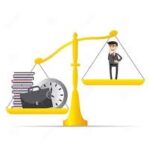

Look at it like this. Imagine your life is a bit like a set of old fashioned balance scales. In one pan go all your resources, (your skills, your knowledge, your confidence; any help that you get from others). In the other pan go all the demands on you to perform, (from your family, your boss, your friends, yourself, whoever). If you don’t have enough resources the scales tip out of balance. Similarly, if the demands on you are excessive then again the scales tip out of balance. If the demands on you exceed your ability to meet them then the inevitable result is that your anxiety levels will rise.

When anxiety gets too intense, when it goes on for too long, or if people find themselves having anxiety attacks without any obvious causes, then this is clearly a ‘bad thing’. It is usually argued that anxiety as a condition of ‘clinical interest’ arises when stress starts to overwhelm the capacity of people to cope and it becomes psychologically destructive. Anxiety at this level interferes with people’s ability to manage both life’s demands on them and their own demands on themselves. If the pressure gets too much to bear, then people lose the ability to get by, to be able to handle their lives. This is the point when psychotherapists start talking about anxiety as a ‘psychological disorder’.

So what’s the answer? Clearly if your personal ‘demands/resources scales’ are out of balance then there are only two ways to go. Reduce the demands or increase the resources. However, making either of those changes is not as easy as it seems. All too often people feel trapped by their circumstances, confined in their own emotional ‘prisons’. This is when psychotherapy comes into its own. As opposed to counselling, psychotherapy is all about problem solving; about altering ways of thinking about life’s problems; about doing something different about them. Psychotherapy is about leaning new ways to be. That includes finding out how to stop being a ‘mustabator’. One very effective way of doing that is to get into the habit of regularly using a self-management technique called ‘Relaxation Therapy’. I’ll be talking more about that in my next Blog.